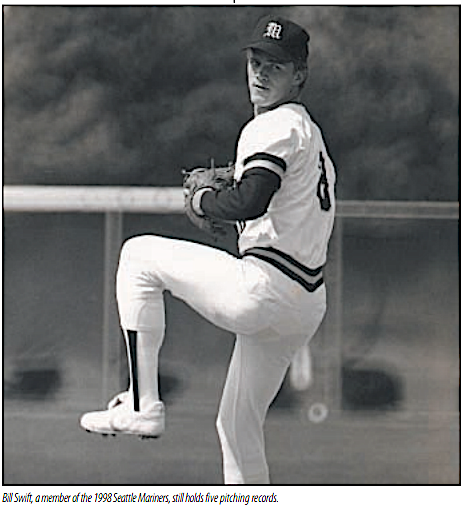

When Bill Swift was just beginning a career that would ultimately establish the South Portland native as a dominant Major League pitcher, his father, Herb Swift, was inducted into the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame.

Now, 24 years and 94 big league victories later, the son takes his inevitable place on the roster of the Pine Tree State’s all-time best.

He is Maine’s winningest major league pitcher.

All Bill Swift ever needed was an opportunity. All he ever wanted was to play somewhere - anywhere. A statement Bill made near the end of his career provides an insight into his high performance, low ego approach to the game.

“If I have to go to the bullpen and stay there until they need a fifth guy.

that’s fine, he said.” Swift was then 37 and in his second tour with the Seattle Mariners. Swift, whose trademark slider was described by pitching coach Stan Williams as “superb”, was passed over by the Mariners who gave him his unconditional release.

Over a 1 3-year Major League career’ Swift had pitched for three teams, fulfilling the brilliance he flashed at the University of Maine for legendary coach John Winkin. Swift was 26-7 for the Black Bears.

He pitched for Team USA at the World Championships in the 1982 and 1983 Pan American Games and for the 1984 United States Olympic team.

He was selected by the Minnesota Twins in the second round of the 1983 free-agent draft but did not sign. The following year he was the second pick overall of the Seattle Mariners in the free agent draft.

Called up by the Mariners after two months with Double-A Chattanooga, Swift pitched five shutout innings in relief to receive credit for the win in his first Major League appearance at Cleveland on June 7th.

He made his first start June 11 against Chicago and was 2-1 in his first

three decisions.

Swift remained with Seattle through 1991, winning 40 games. He was 6-4 in his penultimate season with a club-low 2.90 ERA including a 0.50 mark in June.

There was a frightening moment: on August 5 he was struck in the forehead by a line drive off the bat of Gary Gaetti of Minnesota Swift made a total of eight starts that year (3-2, 2.10) before returning to the bullpen. He had a 1.34 ERA at the Kingdome.

In 1992 Swift was traded to San Francisco and compiled a 10-4 record for the Giants. The following season established him as a premier Major League pitcher.

With a record of 21-8 in 1993, Swift finished second to Atlanta’s Greg Maddux (119 to 61) in the Cy Young voting.

He was among National League leaders in several pitching categories, including third in wins, fourth in ERA (2.82), sixth in winning percentage (.724) and fifth in opponents batting average against (.220).

Swift ran off winning streaks of seven, six, four and three games. He yielded two runs or less in 20 of his 34 starts, including eight starts in which he allowed no earned runs.

As evidence of the athleticism he demonstrated at South Portland and the University of Maine, Swift had 21 hits in 80 at-bats. The 21 hits surpassed the club record of 20 (20-123) set by Juan Marichal in 1960.

Swift was traded to Colorado in 1995. After three seasons with the Rockies (14-10) he returned to Seattle where he was 11-9 in his final Major League season. Bill is married to Michelle, and the proud father of three lovely daughters. Bill now lives in Scottsdale, Arizona.

(NEWS CENTER) — Mainers followed the career of Billy Swift from his freshman year at the University of Maine. The South Portland star was part of a club that went to the College World Series. John Winkin converted the outfielder into a pitcher and a star was born.

Using a nasty sinker, Bill led the Black Bears to a third place finish at the College World Series. The Black Bears made the tournament four straight years.

From Society for American Baseball Research

This article was written by Bob LeMoine

Billy would become a source of pride for his hometown, pitching in the College World Series, the Olympic Games, and 13 seasons in the major leagues. The soft-spoken kid compiled a 94-78 record, and once was runner-up for the National League Cy Young Award.

Herb made billboards for a living to support his large family. “We struggled a little bit,” Billy remembered. “We didn’t have the best of everything, but my parents did good for as many kids as they had to feed. I wasn’t embarrassed.”6 He learned baseball from Herb, who had once been a left-handed pitcher for the Portland Pilots, a Class B farm team of the Philadelphia Phillies, in the New England League. But the rigorous Mainer would pitch anywhere for a few bucks. “I'd pitch doubleheaders. I had a rubber arm. Fifteen dollars a game,” Herb remembered. “Teams would pick me up to pitch for them. Barnstorming. All around Maine. I was all junk. A lefthander, all over the place, no control. A guy would yell, ‘Let me see your fastball.’ I'd say ‘That was it.’” When Billy was born, Herb named him after the greatest Red Sox player of them all. “I named him after Ted Williams. We'd used up all the names of the saints. I wanted William for Ted Williams. My wife wanted Charles. That's his middle name. William Charles Swift.”

Herb taught Billy how to pitch early on, using some unorthodox methods. “I had him throw a short distance. Then, after he was throwing pretty well, I moved back a few steps. I wanted him to have control. I used a workout with him that I always had used. Had batters stand on each side of the plate and had him pitch between them. The key is making sure the batters don't swing. They'd kill each other.” Herb also taught his son lessons about humility. “I always told him, no matter how great you think you are, let someone else tell you,” Herb said. “If you pat yourself on the back, you might break your arm.”

Comentários